The Sienese Crete, the Art of Landscaping

It is no coincidence that many of the shades

of the colour brown, in any box of colours, whether they be tempera,

water-colours, pastels, or oilpaints, have Italian names: terra cotta, terra di

Siena, terra di Siena bruciata. It is in fact from this part of Tuscany, south of

Siena, that the pigments used to make these colours come, pigments so rich that

they were used by all the greatest Italian painters until the advent of

synthetic colours.

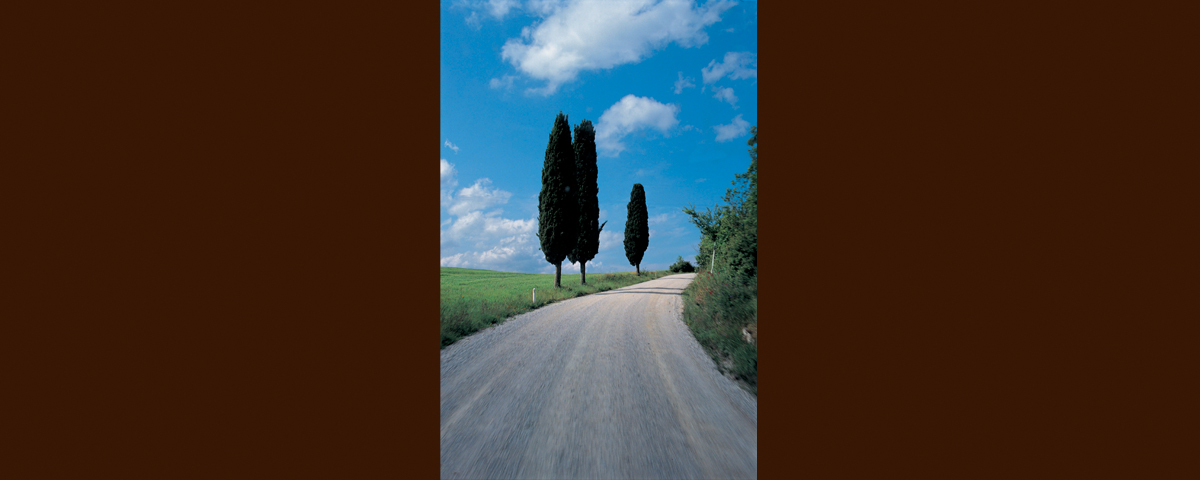

A

lunar landscape, metaphysical if seen in August or September, an undulating sea

of “creta” (clay). Long waves of ploughed land that changes colour every square

metre: from grey, to brown, to ochre, to yellow, to brick. As if it were an

enormous Japanese zen garden, the ploughed furrows snake up and down the hills,

twisting back on themselves, creating fascinating graffiti.

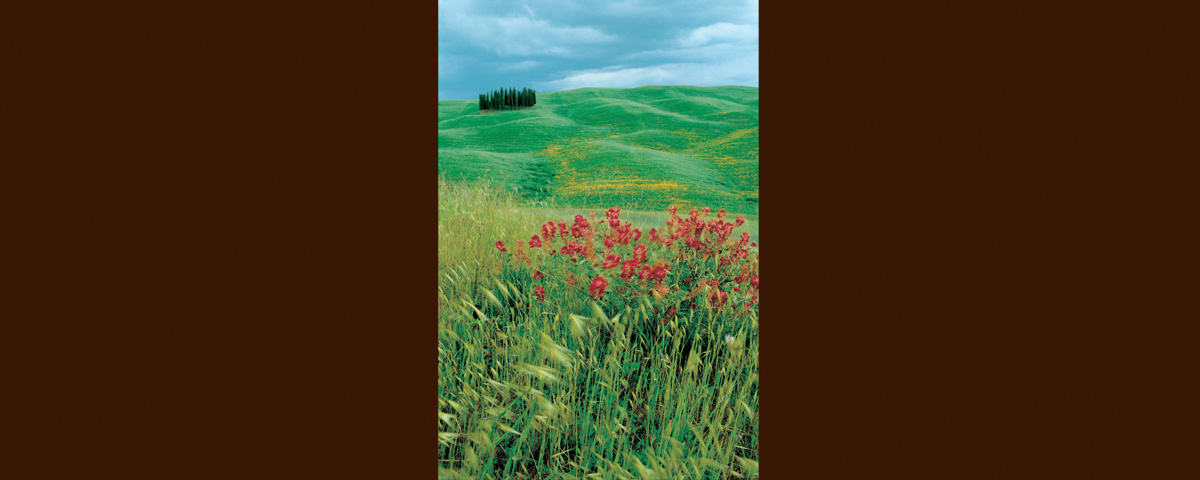

With

the spring, in April and May, the electric green of the young grain transforms

the landscape into velvet cloth waving in the wind as far as the eye can see.

Here and there is a touch of pale yellow, or of magenta, depending on whether

the crop is rape, lucerne or mustard.

It is no coincidence that many of the shades of the colour brown, in any box of colours, whether they be tempera, water-colours, pastels, or oilpaints, have Italian names: terra cotta, terra di Siena, terra di Siena bruciata. It is in fact from this part of Tuscany, south of Siena, that the pigments used to make these colours come, pigments so rich that they were used by all the greatest Italian painters until the advent of synthetic colours.

A lunar landscape, metaphysical if seen in August or September, an undulating sea of “creta” (clay). Long waves of ploughed land that changes colour every square metre: from grey, to brown, to ochre, to yellow, to brick. As if it were an enormous Japanese zen garden, the ploughed furrows snake up and down the hills, twisting back on themselves, creating fascinating graffiti.

With the spring, in April and May, the electric green of the young grain transforms the landscape into velvet cloth waving in the wind as far as the eye can see. Here and there is a touch of pale yellow, or of magenta, depending on whether the crop is rape, lucerne or mustard.